I’m kicking myself for not having read Henry Petroski’s, The Evolution of Useful Things sooner. Since reading, I’ve focused much more on small iterations and attempting to marginally improve my designs. My goal at the end of each day is to have a prototype that works and is slightly better than it was previously. Whatever is left wanting, I attempt to fix next. The result is a more fluid (and fun!) process than trying to mentally conceive of a working concept all at once. I’m also finding that I’m getting what I want out of a design.

The main premise of the book is this: Conventional wisdom says “Form Follows Function” – more easily understood as, “the shape of an object is determined by it’s intended use.” Was the paperclip created in the shape it was because the designer knew ahead of time it had to be that shape? Petroski argues we as a material culture view designed objects in this way when in fact, “Form Follows Failure.” An object’s shape is essentially the outcome of iterations of failed attempts to achieve the desired function. An object’s shape is merely a by-product of when things finally go right. Petroski points out:

“They do not spring fully formed from the mind of some maker but, rather, become shaped and reshaped through the (principally negative) experiences of their users…clever people in the past, whom we today might call inventors, designers, or engineers, observed the failures of existing things to function as well as might be imagined.”

Inventing then, is not some erudite task for intellectuals with a background in calculus. It is more commonly the result of regular people who work simply in a domain where they have some knowledge and, having perceived some failed function in a tool (or wishing the tool existed), are so annoyed that they actually choose to do something about it. The inventor’s chronic need for better is thus society’s gain.

As a chronically annoyed person, I believe this urge for advancement in one’s art faces a new challenge today: We live in a period of time where “better” can be purchased relatively quickly. This can lead to what I call “design by purchase.” For years I would find myself waiting around for weeks for that new part to come in the mail, only to find it didn’t pan out the way I’d hoped. Now, by allowing the work to evolve by making a small, marginal improvement today, creativity finds a way to make do with what materials are laying around and, in the process, this keeps the real requirement in view at all times. This principle objective, according to Petroski, needs to be expressed negatively:

“Design and invention are a fundamentally negative process.You do not have to satisfy all requirements and usually some requirements are incompatible. It is better to weed out irritants over time through each successive iteration.”

Finding the real requirement worth satisfying is essential here. A common slippery slope is something to the effect of, “I need a widget that does X. Ok, so I’ll need to machine the widget out of material Y. Ok, so I’ll need to purchase a machine capable of doing the routing. Ok, I’ll need a dust collector for the machine.” and so on…

But this will usually stray from the original ask. A better approach is, “Why do I need a widget that does X? Is there another way to achieve the same result without improvements to my manufacturing capability?” What once presented as a real requirement can often prove to be a red herring. And trust me, red herrings can last years.

Sometimes though, the only answer is to obtain a deeper knowledge of the art or to improve manufacturing capability. Seemingly simple devices of yore can strike you as odd it hadn’t been invented sooner. Underlying the creation of any object is an interplay of materials science, manufacturing capabilities, and some party having made a degree of investment in those capabilities. For the paperclip, advances in wire bending in the late 1800’s such that the wire would not simply unravel, but instead keep it’s shape were critical to the success of paperclips coming to market. Petroski writes:

“Thus understanding the fundamental behavior of materials and how to employ them to advantage is after a principle reason that something as seemingly simple as a paperclip cannot be developed sooner than it is.”

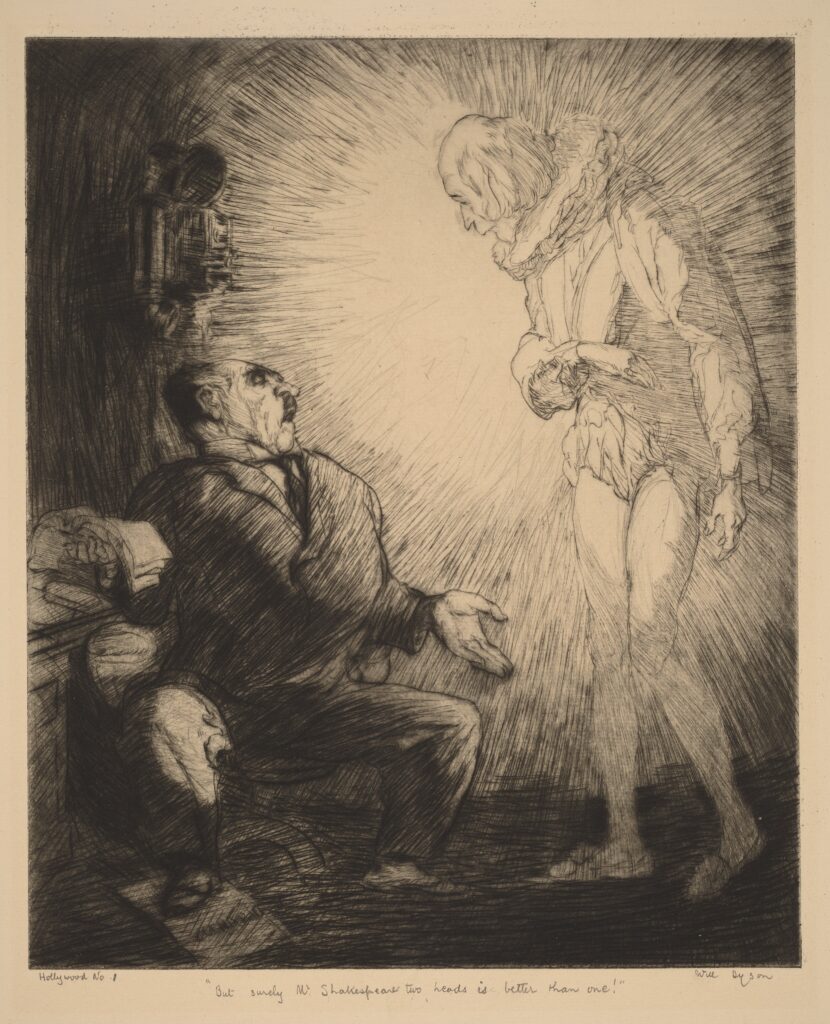

And once it is possible to manufacture the object, what does better look like? I’ve read countless patents on musical instrument pickups dating back to the 1930s. Each inventor must have had some feeling that what she created was indeed the “best.” Why else go through all the trouble? For Petroski, being the “best” isn’t the point, nor is it what produces a successful design:

“As with the Gem paperclip, it seems the design that ultimately wins out is the one that succeeds at getting the requirements right and does the job satisfactorily but does not need to be ‘perfect’ or ‘best’, especially if it’s form is a pleasing rounded and natural appearance that gives it a distinctly human feel in view of it’s competition.”

So don’t aim for “best.” The takeaway from The Evolution of Useful Things is to just make something slightly better. It is to discover true requirements by expressing needs in negative terms based on what is currently unsatisfactory. Do not aim for perfection. Finally, if nothing leaves you wanting, concentrate on making it more human. Therein an invention becomes what it was always meant to be, not a merely tool, but a transcendent object of desire – the product of an inventor’s love and will made visible in the world.