The other evening I took a hot bath. As I moved my forearm at the transition zone between dry skin and hot water, I remembered a line from the Heart Sutra, “The five senses are completely empty in nature.” It’s clear enough we understand the world through our sense organs be it our tongue, eyes or skin, but how often do we truly appreciate that? If you touch a table near you, sandwiched between your hand and the table is your sense of touch. The bath was pleasant because I’m human and not say, an oceanic snail, which would not find it so delightful.

If you follow the existentialist bath down the drain, what happens to ethics and what it means to live a meaningful life? Should we just take baths all the time? (yes.) What about the snails? Can we judge lions? Most of us would find a female lion ripping apart a yak at least somewhat appalling, but for the lion, according to her senses, she’s achieving a great good. If lions could communicate with us, they would probably say killing yaks is revered much like we revere those who create fine works of art. What’s going on here?

What is “delightful”, what is “good”, and how human meaning is derived from human sense-based notions are the area Abraham Maslow tried to resolve in his lifetime. In his book Towards a Psychology of Being, he brings up a clever German expression which encapsulates this nicely: Funktionslust which translates to, “A sense of joy or well-being an animal (including a human) gets from doing that which it is meant to do.”

Those who have heard of Abraham Maslow are probably most familiar with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. In essence, the hierarchy of needs indicates that we humans go through lower levels of satisfying our basic needs until we are ready to aspire towards something higher until we self-actualize. We go from being hungry for food to being hungry for meaning and deeper fulfillment.

One problem I have with self-actualization today is how co-opted it has been by market forces in order to sell self-actualization – be it through self-help courses, lifestyle type products – and so on. If it is something we need then the market attempts to sell it. It’s by this process, as has been said recently, that “capitalism absorbs its own critiques.”

But, as Maslow puts in Towards a Psychology of Being, the aim is much more self-contained and immaterial:

“[Those who self-actualize] are the laws of their own inner nature, their potentialities and capacities, their talents, their latent resource, their creative impulses, their need to know themselves, and to be more and more aware of what they really are, of what they really want, of what their call or vocation, or fate is to be.”

If we are to live a meaningful life – one that is beyond simple survival or pleasure, what do we need to do to figure out what we really want? The key is in the wording “to be more and more aware…” We simply do not start out knowing and we spend our whole lives reshaping this awareness. I’d like to relate a quick story that happened recently which greatly shaped my understanding of what I want.

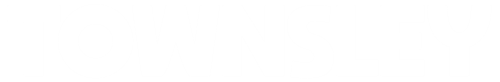

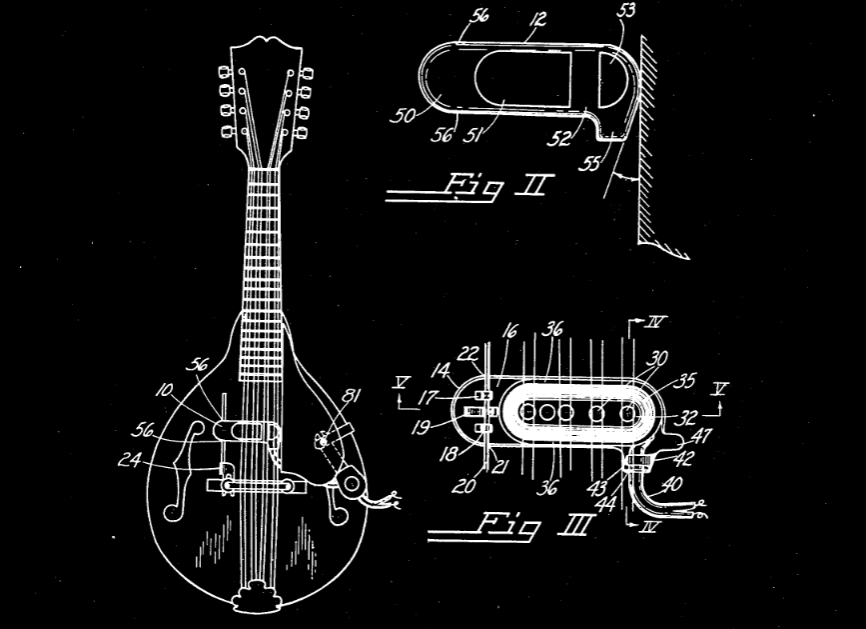

Last weekend, I entered a mandolin contest. I’d spent a month in preparation for it deciding to tackle a difficult piece most people are familiar with, Scott Joplin’s The Entertainer. I learned the full thing note for note on mandolin and so did my friend and fellow Resonaut, Troy on guitar. We meticulously planned it out. The prize for first place was $500 and I was rubbing my hands with assured victory. What I didn’t consider was who my audience (and judges) would be: bluegrass people. Everyone else in the contest played songs the judges knew. They just played fast and clean and didn’t aspire to the heights of what I’d done.

In the end I didn’t even place. I was crushed and thereafter spent several days in real despair. “How could I have worked so hard for no one to see or appreciate what I did? Don’t they know I’m great?” rang in my head incessantly. I did not make excuses for myself, cry foul-play, and didn’t try to simply push those feelings down because there was a deeper reason for my pain. Underneath a simple contest failure was a deep misunderstanding about who I thought I was.

I was walking around my entire 18 year mandolin journey wanting people to believe I was great and believed that winning a contest would prove that. There amid what was truly meaningful to me, the pursuit of the sublime in music, was something that had to go: needing people to believe I was great. One viewpoint would be to say “well do X and Y differently next time and play what the judges want in order to win.” But there are times when you shouldn’t get up. That can be hard when an activity that is so close to what is meaningful is not meaningful. When the pain is worth it, we know how to get back up. Maslow puts it best,

“The answer I find satisfactory is a simple one, namely that growth takes place when the next step is subjectively more delightful, more joyous, more intrinsically satisfying than the previous gratification with which we have become familiar or even bored, that the only way we can ever know what is right for us is that it feels better subjectively than any alternative. The new experience validates itself rather than by any outside criterion. It’s self justifying and self-validating.”

Having spent a while reflecting on my defeat, I believe I have a deeper sense of where I want to grow next. I hope this is helpful and provides some context for someone going through something similar – whichever art they aspire to. It’s worth the struggle.